Abstract

From 2025 onward, Tokyo has implemented one of the most ambitious urban climate policies in the world: mandatory rooftop solar photovoltaic (PV) installation for new residential buildings. While the policy is often portrayed as a decisive step toward decarbonization, this article argues that its actual role is more limited — and more specific — than commonly assumed.

Using quantitative insights from the Net Zero Australia (NZAu) project, this paper examines the structural constraints of distributed urban solar energy and clarifies what such policies can realistically achieve. The analysis is forward-looking by design, aiming to provide a record against which future outcomes can be evaluated.

1. Policy Intent and Internal Rationality

Tokyo’s mandatory rooftop solar policy has a clear and internally consistent rationale:

- Increasing renewable energy adoption in dense urban areas

- Locking in energy efficiency at the construction stage

- Reducing household-sector CO₂ emissions

From a building-regulation perspective, the policy is economically rational. Installing PV systems during construction is typically cheaper than retrofitting, and rooftop solar remains one of the few viable renewable options in highly urbanized environments.

However, rational design does not imply systemic sufficiency.

2. Quantitative Limits Consistent with NZAu Findings

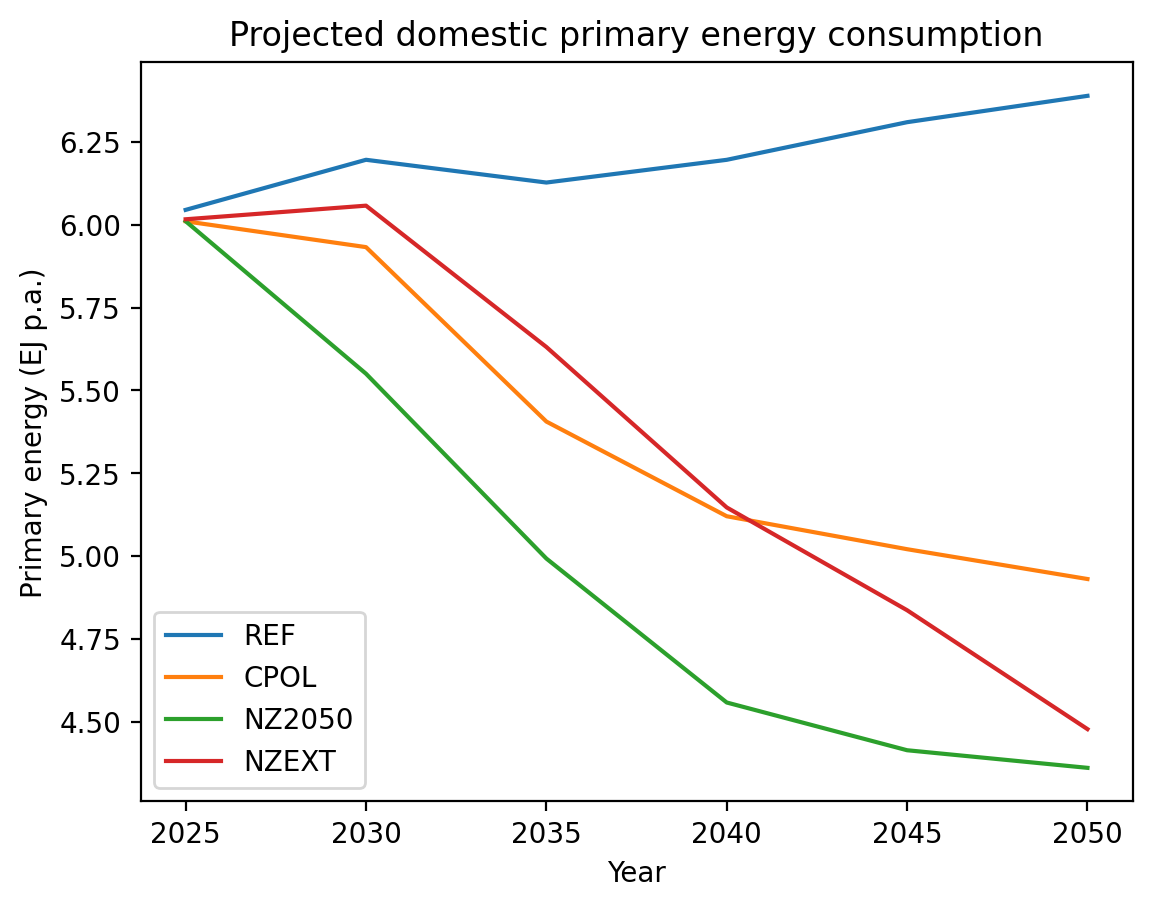

Figure 1. Projected Domestic Primary Energy Consumption (NZAu Scenarios)

Figure 1 shows that even under net-zero pathways, total primary energy consumption does not increase dramatically. Reductions stem primarily from structural demand changes — electrification and efficiency — rather than sheer expansion of renewable supply.

This finding is crucial: decarbonization is not primarily a supply-side volume problem.

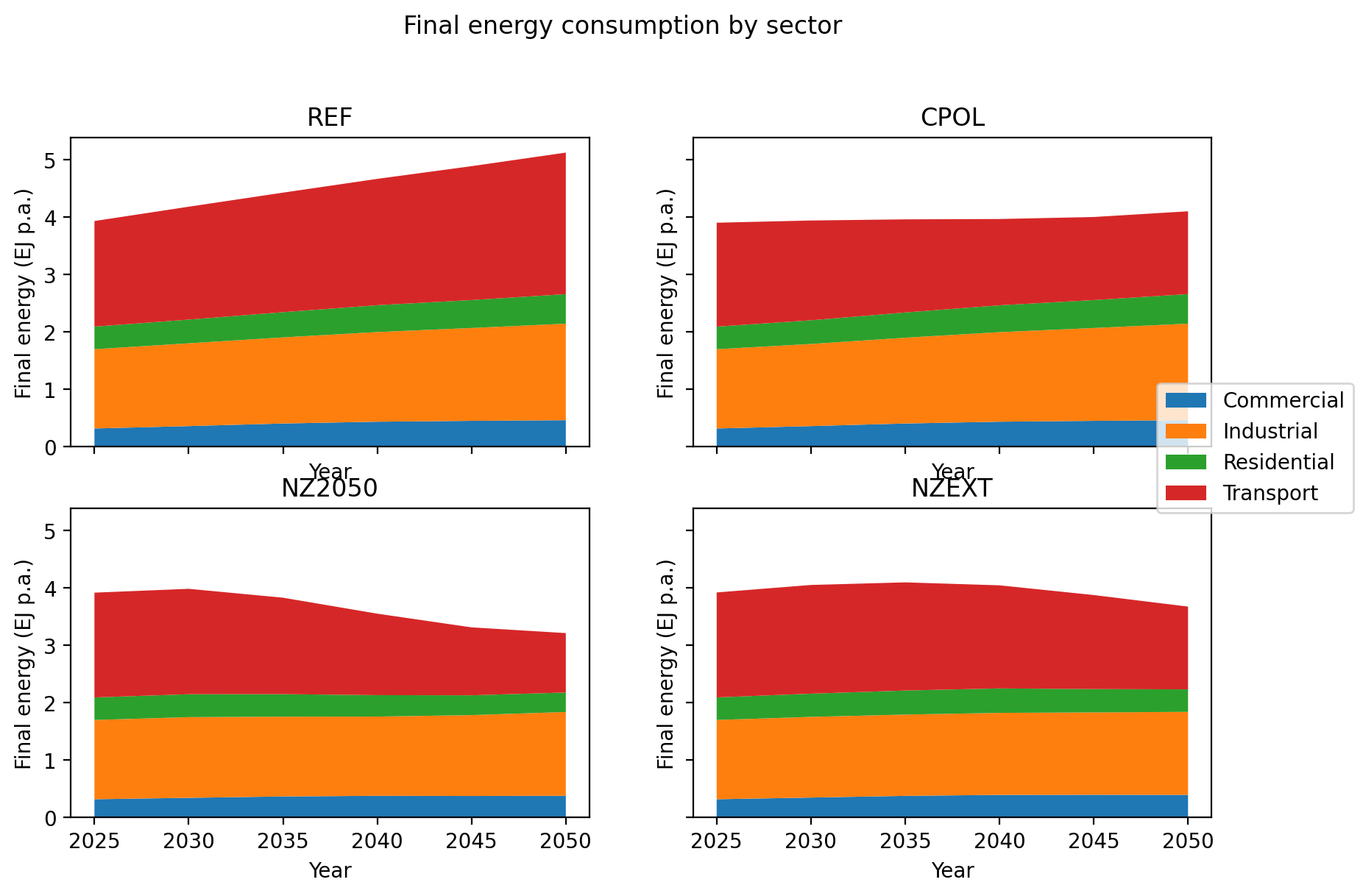

Figure 2. Final Energy Consumption by Sector (NZAu)

As shown in Figure 2, the residential sector represents a relatively modest share of total final energy consumption. This structural reality places an upper bound on what residential rooftop solar can achieve, regardless of policy ambition.

Tokyo’s policy therefore addresses only a limited fraction of the energy system by design.

3. Overestimated Expectations for Distributed Energy

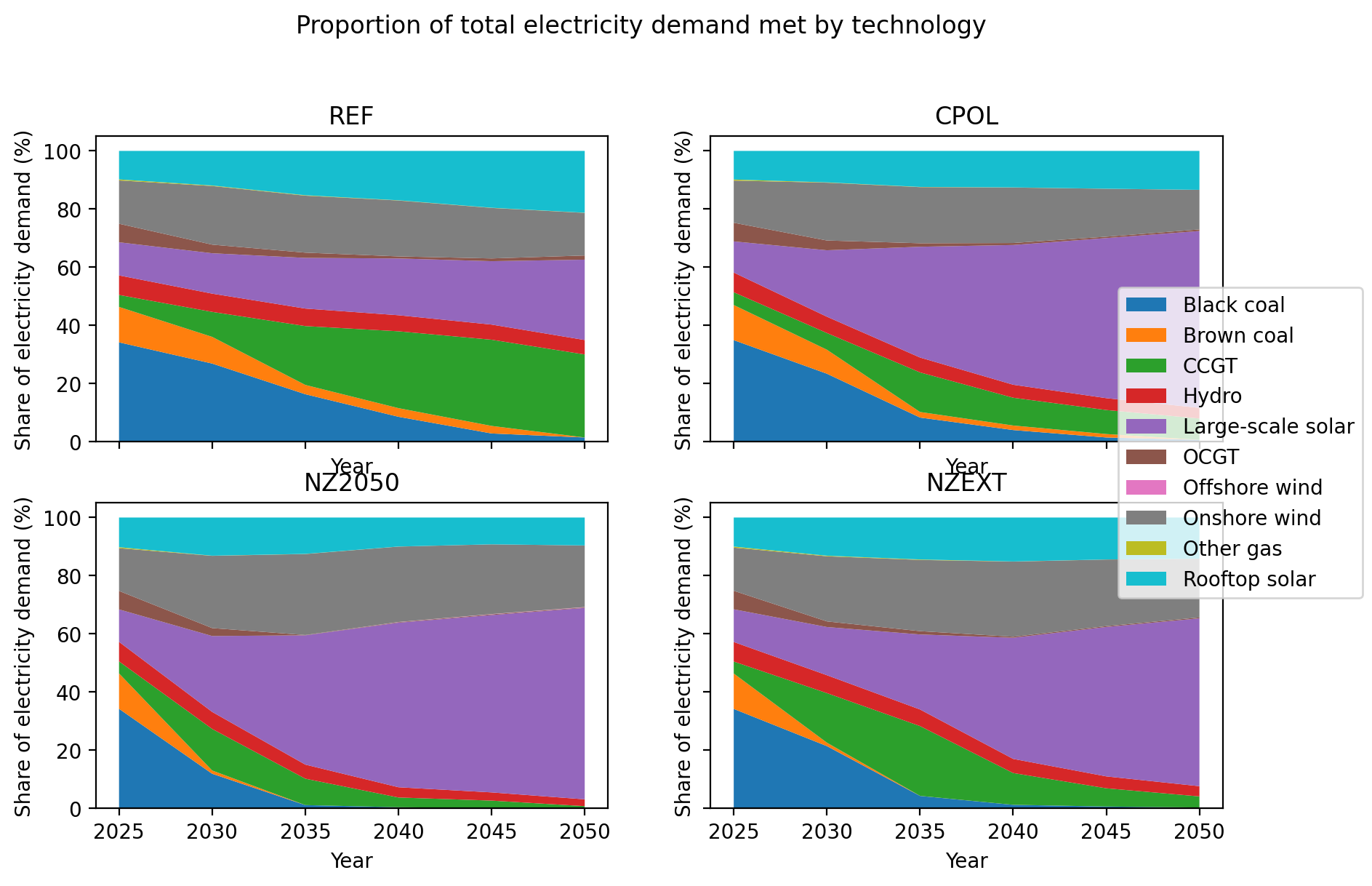

Figure 3. Share of Electricity Demand Met by Technology (NZAu)

Figure 3 demonstrates that even in high-renewables scenarios, electricity systems remain dependent on balancing technologies, storage, and firm capacity. Distributed solar contributes meaningfully, but cannot replace system-level coordination.

This highlights a recurring misconception:

Distributed generation reduces system load, but does not eliminate system complexity. The disappointment that often follows such policies is not evidence of failure, but of unrealistic expectations.

4. The Unavoidable Role of Grid-Scale Infrastructure

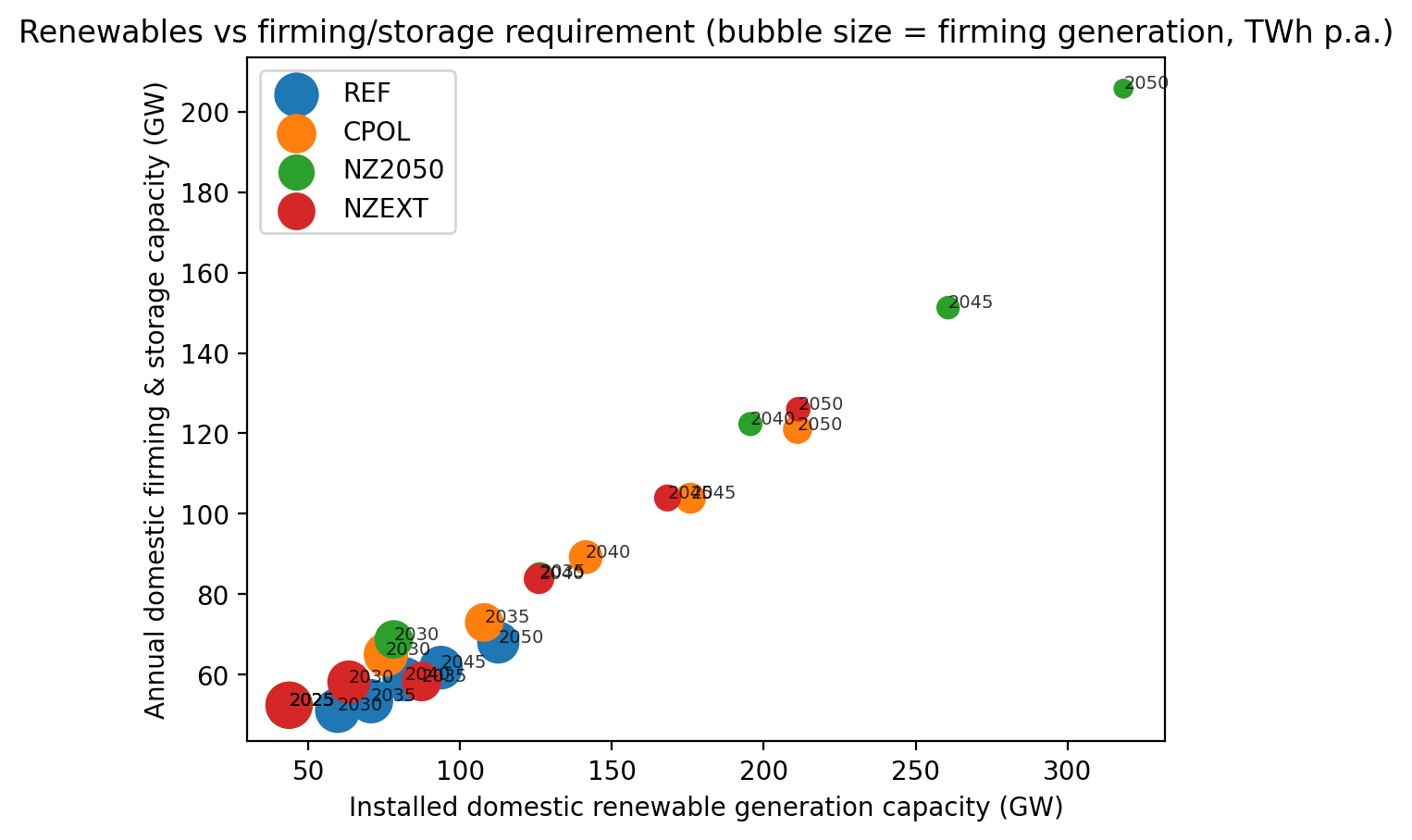

Figure 4. Renewable Capacity vs. Firming and Storage Requirements

Figure 4 reveals a non-linear relationship: as renewable capacity increases, required firming and storage capacity grows disproportionately. In other words, renewable expansion shifts — rather than removes — system constraints.

This directly supports the interpretation of Tokyo’s policy as a complement, not a substitute, for centralized grid infrastructure.

5. Construction Feasibility as the Hidden Constraint

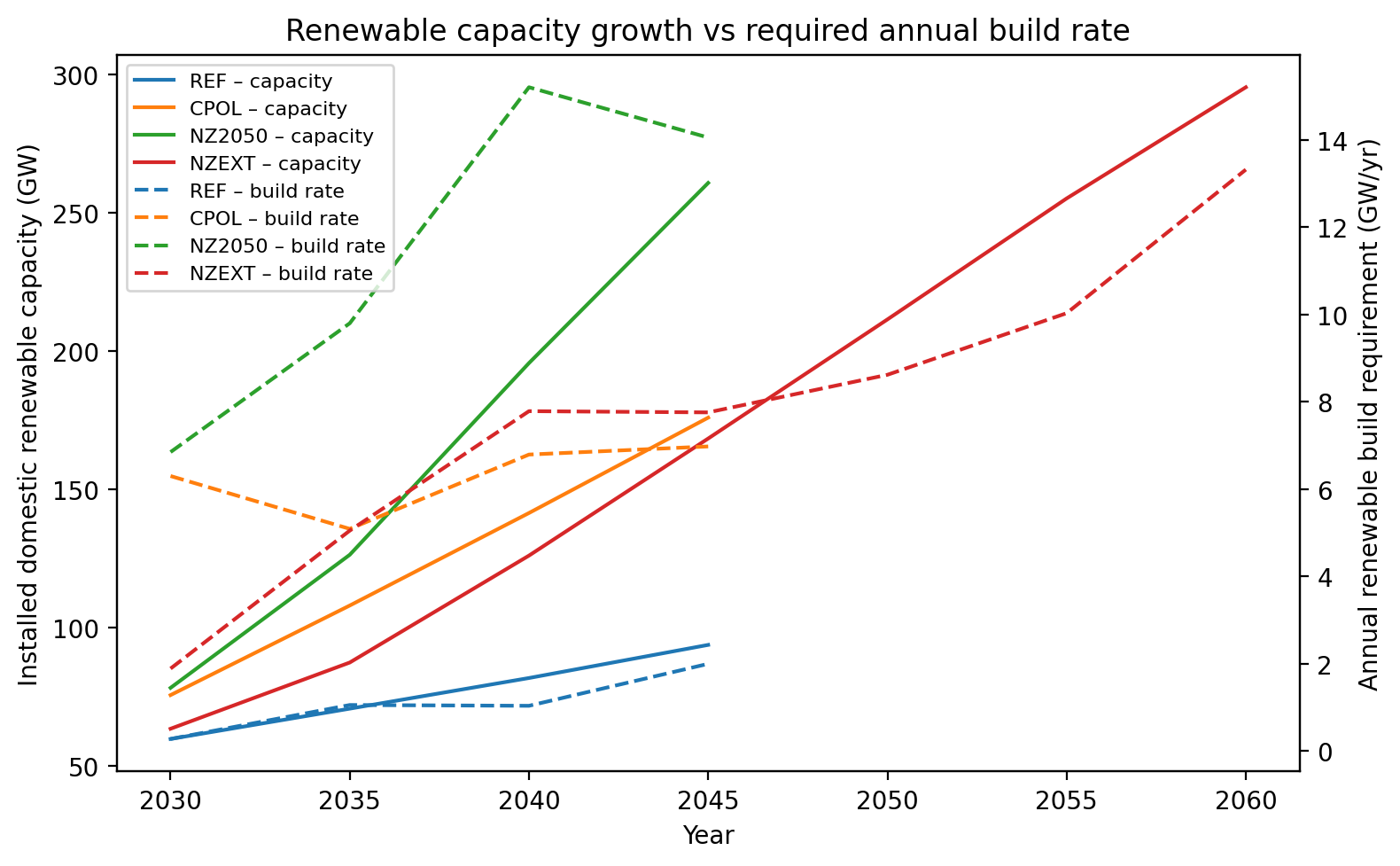

Figure 5. Renewable Capacity Growth vs. Required Annual Build Rate

Figure 5 highlights a critical but often overlooked issue: construction speed. Achieving net-zero pathways requires annual renewable build rates that significantly exceed historical precedents.

This explains a key political reality: policies that avoid direct intervention in grid-scale infrastructure are often preferred because they minimize construction risk, coordination costs, and political exposure.

6. Why “Grid-Neutral” Policies Are Politically Attractive

Tokyo’s policy deliberately avoids direct engagement with transmission networks or utility-scale generation. This is not accidental.

Large-scale grid interventions involve:

- Long construction timelines

- Complex stakeholder coordination

- High political accountability for failure

By contrast, building-level regulations:

- Localize impacts

- Distribute risk

- Produce immediately visible outcomes

Such policies are therefore safer — but also inherently limited.

Conclusion: Tokyo Is Not an Outlier — It Is on the Same Trajectory

Despite major differences in geography and institutional design, Tokyo’s rooftop solar mandate and Australia’s delayed energy transition analysis converge on the same structural conclusion.

- Distributed energy is necessary.

- Distributed energy is not sufficient.

- System-level decarbonization ultimately depends on infrastructure delivery.

Off-grid systems operate independently of external conditions. They therefore provide a practical and effective way to distribute risk in an environment where large-scale infrastructure cannot be assumed to arrive on schedule, and where plans may be altered by disasters, accidents, or other disruptions.

In this sense, off-grid is not an ideological position. It is a rational design response to structural uncertainty in modern energy systems.

Closing Note on Methodology

This analysis intentionally avoids retrospective judgment. It is written to be evaluated against future outcomes, using publicly available modeling and physical constraints. Whether the conclusions hold will be determined not by rhetoric, but by infrastructure built — or not built — over the coming decades.