1. Political background: why Australia doubled down on climate policy

For a long time, Australia was seen as a “climate laggard” among advanced economies: a major exporter of coal and LNG, with a domestic power system heavily reliant on fossil fuels, and politics often gridlocked over climate targets.

That changed with the 2022 federal election. The Labour Party campaigned on a strong climate platform, and the election was widely described as a “climate election”. The new government pledged:

- Net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050

- A 43% reduction in emissions by 2030 compared with 2005

- Roughly 82% renewable electricity by 2030

In other words, Australia moved from “whether to decarbonise” to “how fast can we decarbonise” in just a few years. Ambitious deployment of solar, wind, storage, and new transmission infrastructure became the official roadmap.

Yet political consensus does not automatically translate into physical feasibility. This is precisely where NZAu’s modelling comes in: it attempts to quantify the gap between stated targets and what can realistically be built, permitted, and operated on the ground.

2. What Net Zero Australia’s modelling actually says

NZAu is not a government agency or NGO campaign. It is an independent modelling project that tests a wide range of scenarios for how Australia could reach net-zero while maintaining energy security and international competitiveness.

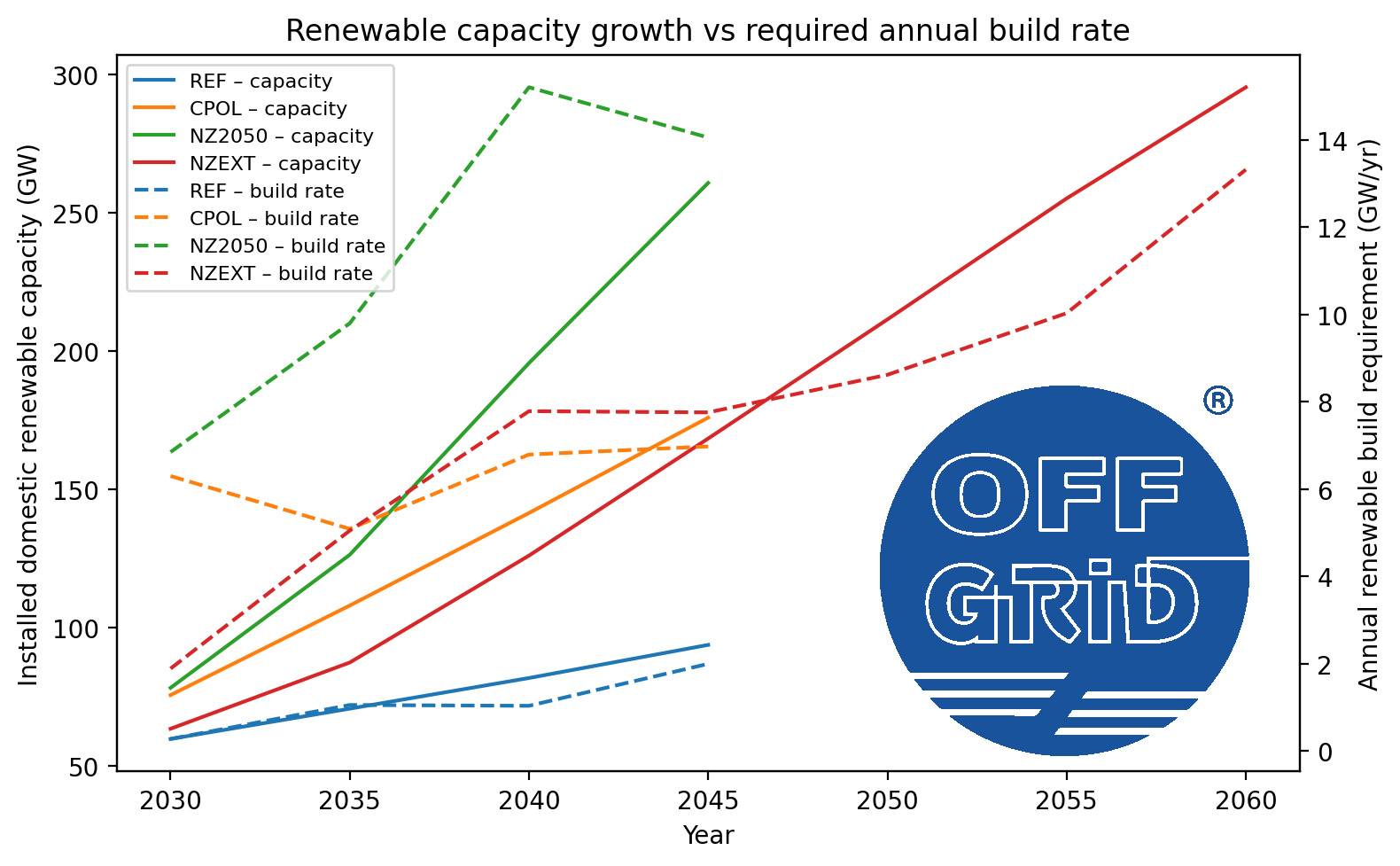

The headline that “Australia may be up to 10 years late” refers to the finding that even under ambitious build-out assumptions, reaching an 82% renewable share in the power mix by 2030 is very challenging. NZAu’s pathways indicate that:

- Large-scale solar and wind capacity would need to increase several-fold in less than a decade, across multiple states and grid regions.

- On top of generation, Australia would require roughly twice today’s transmission capacity, plus new hydrogen and CO₂ pipeline infrastructure.

- Even assuming optimistic timelines for permitting, construction, and grid connection, some scenarios naturally push the 82% renewables milestone into the late 2030s.

The message is not that “net zero is impossible.” Rather, NZAu’s analysis says: if you take land use, supply chains, labour, and community acceptance seriously, the path to net zero looks more like a staircase than a straight line.

3. Physical and social constraints: where the bottlenecks really are

When people talk about “delay,” they often focus on technology: panel efficiency, battery costs, or hydrogen round-trip efficiency. NZAu’s work points elsewhere.

3-1. Land and siting

Utility-scale solar and wind require vast land areas, transmission corridors, and access roads. In practice, these are constrained by:

- Competing land uses (agriculture, conservation, mining)

- Environmental regulation and biodiversity concerns

- Local community opposition and project fatigue

In remote regions, grid connection itself can be a limiting factor. Projects that look optimal on a map may be unbuildable within the desired timeframe.

3-2. Grid and infrastructure

Renewables policy often focuses on generation targets: X gigawatts of solar, Y gigawatts of wind. But as NZAu emphasises, without transmission and storage, those gigawatts are just numbers on paper.

- New high-voltage lines face long permitting and construction timelines

- Substations, interconnectors, and control systems must be upgraded in sync

- Hydrogen and CO₂ pipelines add yet another layer of complexity

In short, the bottleneck is not only “how fast can we deploy renewables,” but “how fast can we rebuild the physical and institutional backbone that supports them.”

4. Why “delay” does not mean “failure”

If the 82% renewables target slips from 2030 to, say, 2037–2040, it may sound like a policy failure. But from a systems engineering perspective, that shift can also be read as a move from “wishful thinking” to “physically implementable pathways.”

NZAu’s modelling suggests that the binding constraints are not purely technological. They are a mix of:

- Grid and infrastructure lead times

- Labour and supply-chain capacity

- Social licence for large-scale projects

- Institutional capability to coordinate many actors in parallel

Seen this way, Australia is entering what we might call a “reality adjustment phase” in its net-zero transition. The targets remain, but the path is being recalibrated to match the actual speed at which steel, copper, land, and people can be mobilised.

5. What this implies for Japan and for corporate energy strategy

Why should Japanese policymakers and corporate decision-makers care about NZAu’s warning of a “10-year delay” in Australia’s transition?

Because the underlying constraints are not uniquely Australian. Japan faces its own combination of land scarcity, complex permitting, and grid bottlenecks—plus a far greater reliance on imported fuels. If a resource-rich country like Australia runs into physical limits, Japan certainly cannot assume a frictionless transition.

For companies, the lesson is simple: do not base your whole resilience strategy on optimistic central plans. Even with strong policy support, large-scale grid modernisation takes time. That lag is precisely where on-site generation, storage, and off-grid architectures start to matter—not as a romantic ideal, but as a practical risk-management tool.

In the next article in this series, we will look more closely at the sectors that NZAu and other studies highlight as critical—particularly buildings, distributed energy, and industrial efficiency—and what that means for concrete investment decisions in Japan.

“What Is Off-grid?” — 3-part series (Japanese & English)

-

Part 1:

What is off-grid? Choosing “自在” — the freedom to be self-sufficient

Japanese / English -

Part 2:

The systems-engineering advantage of off-grid — why microgrids and smart grids are not the final answer

Japanese / English -

Part 3:

How off-grid is actually implemented — architecture of a self-sufficient, distributed, asynchronous system

Japanese / English