1. Recognizing a World Where “We Cannot Predict” Is the Default

“No one knows what will happen a week from now, let alone a year from now.”

This may sound like a cliché, but in recent years we have quietly crossed the threshold where this statement is literally true as a structural condition.

For several decades, the dominant assumption behind globalization was:

“If we centralize rules and infrastructure, and connect everything with networks, we can optimize the whole.”

Supply chains, finance, energy, and information systems were all built on this premise of integration and continuity.

Today, however, the situation is different. Regions are split by conflicts and sanctions; standards diverge; logistics are disrupted by disasters and regulations. The world is no longer “temporarily unstable”; it is structurally fragmented.

In such a world, systems that assume “everything will basically keep working” are fragile by design. What we need instead are systems that are prepared from the outset for disconnection, delay, and partial failure. That is the motivation for discussing autonomy, distribution, and asynchrony as design principles.

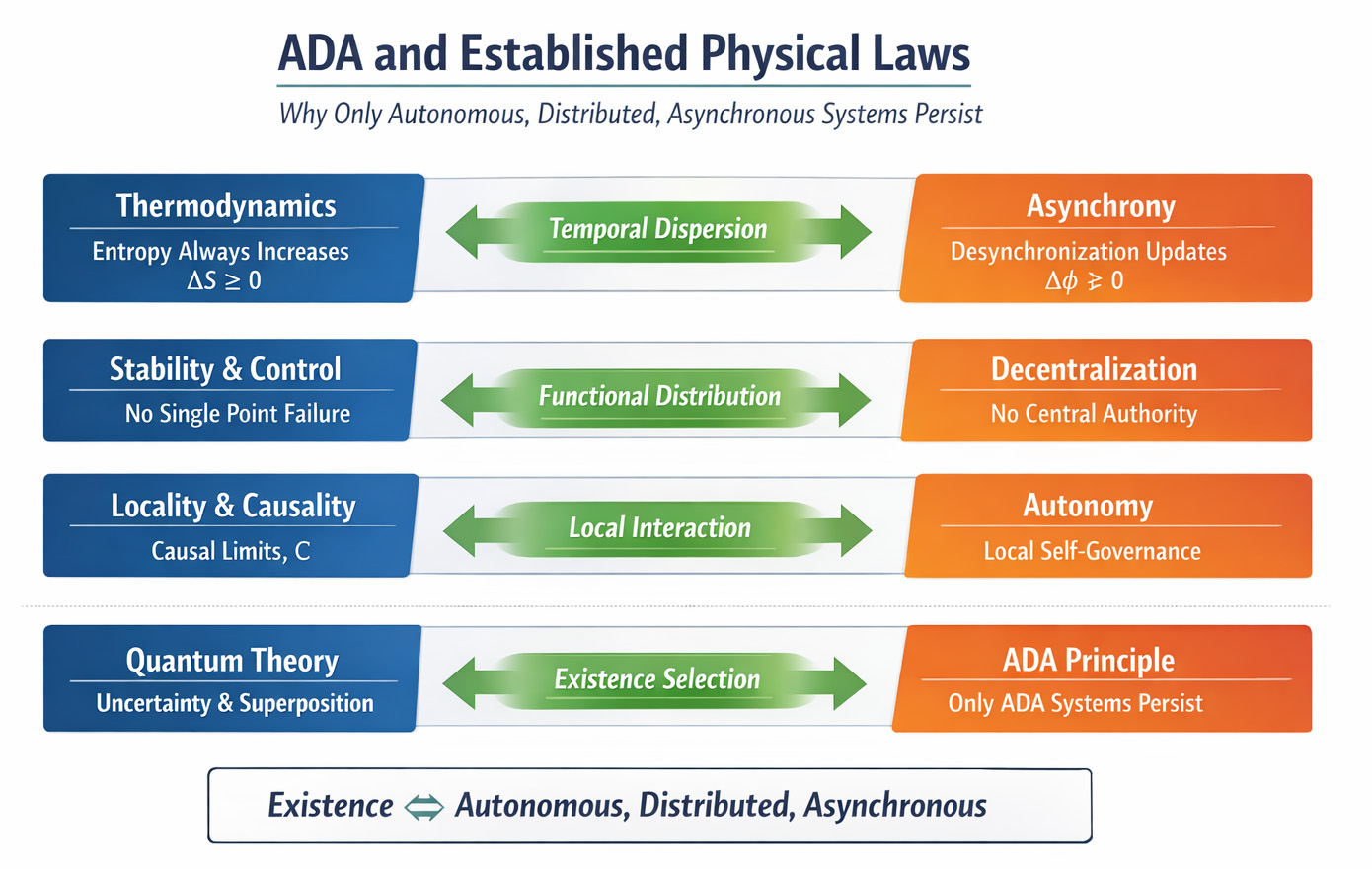

2. Autonomy, Distribution, and Asynchrony as Design Principles

When we speak of a “design principle,” we are not talking about a slogan or value judgment. We are talking about how to place assumptions at the structural level.

Systems that are brittle in the face of change have one thing in common: they assume too many things will go as planned. They assume continuous connectivity, shared schedules, centralized decisions, and stable external conditions.

In contrast, systems based on autonomy, distribution, and asynchrony are designed so that:

- They behave correctly based on local state, without waiting for a central command. (Autonomy)

- Functions and responsibilities are spread across multiple nodes and layers. (Distribution)

- The system does not require everything to run on a single, synchronized timeline. (Asynchrony)

The point is not what labels we use, but whether our systems are actually built so that they can be split, partially stopped, reconfigured, and restarted when necessary. This is the real meaning of design for a fragmented world.

3. What “Autonomy” Means in Practice

Autonomy in this context means that each unit can decide its own state transitions based on its own condition and locally available information. It is not about isolation or selfishness; it is about having the ability to take responsibility for one’s own operation.

In business terms, autonomy means, for example:

- A site or plant can continue minimum essential operations even if headquarters is offline.

- A department can make day-to-day operational decisions without waiting for centralized approval.

- Critical processes can be restarted locally, without relying on a single remote authority.

In equipment and IT systems, autonomy means:

- A production line decides on stop/continue based on local sensors and conditions, not only on an upstream signal.

- An application can fail gracefully in one module without crashing the whole monolith.

- An off-grid power system can maintain supply in an area even when the central grid is down.

Autonomy does not mean “everyone does whatever they like.” It means each unit is structurally equipped to act responsibly within its own domain. That is the smallest unit of resilience in a fragmented world.

4. What “Distribution” Means

Distribution is about avoiding single points of failure. It is the structural decision to “not put everything in one place or one role.”

Examples include:

- Multiple plants or logistics centers that can substitute for each other in emergencies.

- Data replicated across regions so that the loss of one site does not mean total data loss.

- Multiple power sources and routes, instead of a single large substation feeding everything.

Of course, distribution has costs: redundancy, management overhead, and sometimes lower apparent efficiency. But in a world where disruptions are no longer rare events, the question is not “How do we maximize efficiency in normal times?” but rather “What structure gives us tolerable losses and fast recovery when things go wrong?”

Distribution, in this sense, is not a luxury. It is the option value that allows us to keep alternatives open when a part of the world becomes inaccessible.

5. What “Asynchrony” Means

Asynchrony concerns time. In an asynchronous system, not everything moves according to a single shared clock. Different parts can proceed at different speeds, and that difference is tolerated by design.

For example:

- Some processes update in real time, while others batch-process at regular intervals.

- Some sites close books daily, while others report weekly, with systems designed to reconcile the gap.

- Local energy storage covers short-term fluctuations so that demand and generation do not have to be perfectly synchronized at every moment.

Asynchronous systems allow temporary inconsistency, but are designed so that: data and state converge safely over time. This makes it possible for parts of the system to keep running even when others are delayed or temporarily unavailable.

In a fragmented world, insisting on strict global synchronization becomes a source of fragility. Choosing asynchrony is choosing to let the system breathe.

6. Autonomy, Distribution, and Asynchrony in Operations and Equipment

Let us bring these concepts closer to day-to-day operations. When we design plants, logistics centers, and IT systems with autonomy, distribution, and asynchrony in mind, we get structures like the following:

- Autonomous sites: each plant can secure minimum essential power, communications, and data logging, and can continue core operations even when head office systems are impaired.

- Distributed roles: no single person, server, or site holds an irreplaceable function; responsibilities are split and documented.

- Asynchronous workflows: approvals and reporting are designed so that they can catch up later, instead of freezing everything when one path is blocked.

In other words, the system is designed so that “something can always move somewhere”. That is what it means to embed autonomy, distribution, and asynchrony into operations.

7. Autonomy, Distribution, and Asynchrony in Energy and Off-Grid Systems

Applied to energy, these principles naturally lead to off-grid and semi-off-grid architectures. Large, centralized grids assume continuous connectivity and global synchronization. In a fragmented world, this assumption itself becomes a risk.

In an off-grid context:

- Autonomy means each site has its own primary power source and control logic.

- Distribution means power generation and storage are spread across multiple units, not concentrated in a single large plant.

- Asynchrony means each local system operates without requiring strict frequency or timing synchronization with a central grid.

This is not an ideological stance, but a system design consequence: if we start from the premise of fragmentation and design for long-term continuous operation, off-grid architectures emerge naturally as a stable solution.

8. Conclusion — Designing on the Premise of Fragmentation

Autonomy, distribution, and asynchrony are not tools for “overcoming” fragmentation. They are design principles for coexisting with a fragmented world.

Instead of trying to make everything uniform and tightly coupled, we deliberately choose structures that continue to function even when things are not aligned.

That is what it means to design on the premise of fragmentation: avoid unnecessary concentrations, accept time lags, and let different parts decide and move within their own responsibility. In the next steps of this series, we will translate these principles into concrete architectures and products.